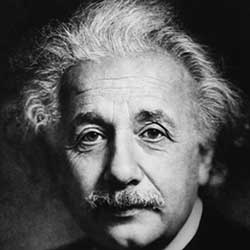

Einstein tried to express these feelings clearly, both for himself and all of those who wanted a simple answer from him about his faith. So in the summer of 1930, amid his sailing and ruminations in Caputh, he composed a credo, “What I Believe,” that he recorded for a human-rights group and later published. It concluded with an explanation of what he meant when he called himself religious: “The most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead, a snuffed-out candle. To sense that behind anything that can be experienced there is something that our minds cannot grasp, whose beauty and sublimity reaches us only indirectly: this is religiousness. In this sense, and in this sense only, I am a devoutly religious man.

Einstein tried to express these feelings clearly, both for himself and all of those who wanted a simple answer from him about his faith. So in the summer of 1930, amid his sailing and ruminations in Caputh, he composed a credo, “What I Believe,” that he recorded for a human-rights group and later published. It concluded with an explanation of what he meant when he called himself religious: “The most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of all true art and science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead, a snuffed-out candle. To sense that behind anything that can be experienced there is something that our minds cannot grasp, whose beauty and sublimity reaches us only indirectly: this is religiousness. In this sense, and in this sense only, I am a devoutly religious man.

People found the piece evocative, and it was reprinted repeatedly in a variety of translations. But not surprisingly, it did not satisfy those who wanted a simple answer to the question of whether or not he believed in God. “The outcome of this doubt and befogged speculation about time and space is a cloak beneath which hides the ghastly apparition of atheism,” Boston’s Cardinal William Henry O’Connell said. This public blast from a Cardinal prompted the noted Orthodox Jewish leader in New York, Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein, to send a very direct telegram: “Do you believe in God? Stop. Answer paid. 50 words.” Einstein used only about half his allotted number of words. It became the most famous version of an answer he gave often:“I believe in Spinoza’s God,” who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.”

Some religious Jews reacted by pointing out that Spinoza had been excommunicated from Amsterdam’s Jewish community for holding these beliefs, and that he had also been condemned by the Catholic Church. “Cardinal O’Connell would have done well had he not attacked the Einstein theory,” said one Bronx rabbi. “Einstein would have done better had he not proclaimed his non-belief in a God who is concerned with fates and actions of individuals. Both have handed down dicta outside their jurisdiction.”

But throughout his life, Einstein was consistent in rejecting the charge that he was an atheist. “There are people who say there is no God,” he told a friend. “But what makes me really angry is that they quote me for support of such views.” And unlike Sigmund Freud or Bertrand Russell or George Bernard Shaw, Einstein never felt the urge to denigrate those who believed in God; instead, he tended to denigrate atheists. “What separates me from most so-called atheists is a feeling of utter humility toward the unattainable secrets of the harmony of the cosmos,” he explained.

Thoughts or questions how to understand Spinoza’s God? lalmeida4141@gmail.com